World Piano Teachers Associates Conferences

New York University Casa Italiana Zerilli Marimo’

Yamaha Piano Salon on Fith Avenue

Carnegie Weill Hall

New York City

Click here for photos.

Jani Aarrevaara, pianist, FINLAND

K. Szymanowski (1882-1937) Variations op. 3 (1901-1903)

F. Busoni (1866-1924) Sonatina No.2 (1912)

Ferruccio Busoni: Sonatina seconda (Kind. 259)

Takuina Adami, pianist, ALBANIA

Ejona Germeni , pianist, ALBANIA

Lecture-recital

The pianistic miniatures of Albanian composers

Tonin Harapi, Simon Gjoni, Cesk Zadeja

Min-Kyung Choi, pianist, KOREA

Wonyoung Chang, pianist, KOREA

S. Rachmaninoff Concerto No.1 in F-sharp minor Op.1

Nathan Carterette, pianist, USA

B. Bartok Improvisations on Hungarian Folk Tunes Op.20

B. Bartok Allegro Barbaro and Improvisations on Hungarian Folk Tunes, op.20

Paul DePass, pianist

ADOLPH VON HENSELT

Carla Giudici, pianist

Hermira Gjoni , pianist, ALBANIA

Jenny Rroi, pianist, USA

EMOTIONS AND PIANO

Soyeon In, pianist, KOREA

S.Rachmaninoff, Variationen von 'Corelli' Op.42

L.van Beethoven, Klaviersonate Op.28, D-Dur

Lotte Jekeli, pianist, GERMANY

"Leos Janacek and his piano cycle ‘In the Mist’"

Gesa Luecker, pianist

Sonata op.27, No.1 by L. v. Beethoven

Nancy Lee Harper, pianist, PORTUGAL

"The Interpretation of Manuel de Falla's Fantasia baetica"

Salvatore Moltisanti, pianist, ITALY

Chie Sato Roden, pianist, JAPAN-USA

CELESTIAL MECHANICS [MAKROKOSMOS IV] (1979)

George Crumb (b.1929)

Ivon Maria Pek Pien, pianist, INDONESIA

“Indonesian Composers”

Anna Rutkowska-Schock, pianist, POLAND

“Elements of Polish folklore in Szymanowski’s piano music”

3 Polish Dances- Mazurek, Krakowiak, Oberek

4 mazurkas Op.50

Atsuko Seta, piano solo, JAPAN

Sonata no.1, Op.22

Alberto Ginastera (1916-1983)

Ning-Wu Du, pianist, CHINA

Peer Gynt (two-piano version)

Valentin Surif, pianist, ARGENTINA

Gennsly Ediansyah Syams, pianist, INDONESIA

Carl Vine (1954-)

Piano Sonata No.1(1990)

“Piano music and Haiku”

Jani Aarrevaara, pianist, FINLAND

K. Szymanowski (1882-1937) Variations op. 3 (1901-1903)

F. Busoni (1866-1924) Sonatina No.2 (1912)

Ferruccio Busoni: Sonatina seconda (Kind. 259)

No matter how far Busoni looks prophetically into the future in his theoretical works (especially in his „Entwurf eines neuen Ästhetik der Tonkunst“, 1907) – by anticipating the upcoming of serial music and even conjuring up microtonal systems – he could never fully take leave of the 19th century as a composer. After 1912, facing the boundaries of atonality, he remained within a "young classicism" (as he himself would call it).

In Sonatina seconda (1912), the second of a cycle comprising six sonatinas (1910 – 1920), Busoni advances farest on the self-proclaimed future of music. Even if the "gestus of classical orderliness is being preserved" here (H. H. Stuckenschmidt),

Generally, two multi-part movements are to be recognized; there are altered reprises, also in theme, whereas the sonatina lacks being thematically built up. It is totally made up if not improvisatory.

The reluctant elements of the free polyphony belt the arrangement of intervals – major and minor second, and their complementary intervals major and minor seventh. The title of the piece is ambigous since it is about the second sonatina as well as that of the second.

Within the evolution of piano music in the early 20th century Busoni's sonatina remains an important pathway leading to the ground-breaking ideas formulated by the Second School of Vienna.

Karol Szymanowski: Theme and Variations, B flat minor, Op. 3

The Variations in B flat minor (Thème Varié), Op. 3, by Karol Szymanowski date from 1903 reflecting the earliest phase of style in the works of this Polish composer.

Szymanowski, who was open to Western and Eastern trends alike, was most strongly influenced by Russian and German music in the beginning, especially by the works of Skrjabin and Reger. In the Variations Op. 3 it is most particularly the power of expression (esp at the end of the piece) that recalls the music of Skrjabin.

Szymanowski's first phase of style culminated in the second sonata, which remained just within the boundaries of conventional major-minor tonality. The 3rd sonata (1917), belonging to the second phase of style, already has dodecaphonic approaches. In this new phase, the composer had got inspired most from Debussy, Ravel and Strawinsky.

The outlines of the Variations Op. 3 are "classic": the most significant melodic and harmonic features of the theme have been preserved in the single variations. There is a huge contrast between the fast pianistic variations (esp the agitato var.) and the slower ones. In the 9th variation the yet grave-melancholic mood changes to major where for the time being we hear a waltz. (Variation No. 3 already was a dance: Andantino quasi tempo di mazurka.) All subsequent variations remain in major (B flat major, with the exception of No. 10 which is in G flat major) The twelfth, and last, variation offers an imposing finale in length as well as in powerful expression evoking ecstasy.

Takuina Adami, pianist, ALBANIA

Ejona Germeni , pianist, ALBANIA

Lecture-recital

The pianistic miniatures of Albanian composers

Tonin Harapi, Simon Gjoni, Cesk Zadeja

I am very happy that I’m here with you today to present something, even only a small part of the Albanian piano music.

The development of cultivated music started in our country much later than in most European countries. The people were fighting to gain their independence until 1912. The occupation lasted for centuries, and if this was not enough, the communist dictatorship deprived the people from the right to be in contact with contemporary music.

In the fifties and sixties a new generation that has studied in east Europe opened the way to cultivate music starting with small character pieces up to symphonies and operas.

Now I will try to present you three of the most important Albanian composers. They were born at the same city – Shkoder - that is the northern city of our country near Montenegro.

Tonin Harapi (1928-1992) wrote music around the years 60 until 90-ties. He takes a place of honor in the Albanian music especially when we evaluate his small character pieces for piano and his vocal romances. His works are “Album for children”, “Album for youth”, Variations, Sonatas, one Rhapsody and four Concerts for Piano and orchestra. He wrote also chamber music as well as two operas.

In his work we come across romantic features, tonal harmony, singing melodies, lyrical and dramatic means of expression by romantics. His music was based in folksongs and dances especially the ones from Shkodra which are so melodious that they remind you of the music of Schubert and his “lieders” in particular.

Very clear melodic lines and pianistic textures help the children to develop a beautiful sound, feeling for color and breath, that are so important both in the training of their musical intuition.

The titles, very appropriate, are like “A little pain”, “Red Apple”, “The joy is back again” etc. The rhythmical element in the miniatures flows naturally along the character, versatile and elegant. Although they all have titles, their fluent musical lines remind us only one, the Mendelssohn “songs without words” or lyric pieces of Edward Grieg.

Simon Gjoni graduated at the Academy of Prague. He was one of the co-founders of the Radio Television Symphonic orchestra in Tirana. As a composer his activity has passed through the song, romance, cantata, suite, ballads, works for piano, clarinet, violin and major orchestral works such as Symphonic dances, Symphonic Poems, Symphonic Suites up to Symphony in Mib.

George Leotsacos, the greek musicologist said for him:

“Simon Gjoni is an excellent composer, a predestined creator, with a profound aesthetics and musical culture, but above all with marvelous human personality, with golden heart in harmony with his refined culture.”

In the Piano Album of this composer we can find 22 works of various genres and diverse characters. The parts are clear in contents and form where the vocal nature of phrasing stands out. The songs “The Snow flower, “Grey eyed” etc, reminds us of such things. But except the artistic values of these parts, from my pedagogical practice, I evaluate their didactic aspect. The musical material is worked carefully by the composer in full conformity with the contents and character of the pieces and is realized with studied factures to the capacity and possibilities for young pianists.

The third composer Cesk Zadeja has a different personality, his music is very intellectual, with his music he can penetrate inside the listener in a different way: his musical lines are created from intonations that seems to you well known but in reality they are very original. He always uses three horizontal lines that not randomly create canonic and polyphonic imitations in right proportions and deep meanings of the musical thought. His bi-tonal harmonic if his works create a fusion dissonant. His music has a dominant potential and personality that is difficult to capture with the first hearing but that are likely to listen again and only then can you find moments that you will like.

Cesk Zadeja is the author of two Piano Albums, many vocal and Symphonic works within them a Symphony, one Opera and two ballets. More concretely with the works that we will present today, at the “Epic sound” of the form of a Prelude and Toccata, you can notice the clearness of the musical thought, the naturalness of the development toward the culmination rich in polyphonic and bi-tonal elements.

Takuina Adami

Min-Kyung Choi, pianist, KOREA

Wonyoung Chang, pianist, KOREA

S. Rachmaninoff Concerto No.1 in F-sharp minor Op.1

Sergei Rachmaninoff (1873-1943) remained a true romanticist and made his way into the twentieth century by expanding upon a distinctly nineteenth-century style of piano playing. Since he was a great concert pianist, his pianistic style and ability are reflected so well in his compositions. He had large hands, able to span a chord of a thirteenth with the left hand and with a remarkable stretch also in the right, spanning a tenth by the lower note with the first finger and the upper note by thumb-crossing. He is always aware of a sense of direction in what he played and of a point of culmination, of whatever kind, the whole executed with impeccable precision, a fine singing tone, where this was called for, rhythmic energy and a clarity of definition, even in passages of the great complexity.

His first concerto, written in 1890 and revised in 1917 just before he left Russia for good, was finally published in 1920 with considerable thinning not only of its texture but also of the actual material from the first version. Still, this concerto, his favorite, exhibits all of Rachmaninoff’s compositional strengths. Its melodic appeal is supported by sonorous harmonies with florid decoration and very strong taxing passages.

The first movement opens with a brass fanfare, followed by a rapid solo passage of descending octaves and the weighty chords that we might have expected. The orchestra introduces the first theme, taken up by soloist. There is a second theme, marked meno mosso, and the opening of the movement has a part to play in what follows, notably in the extended cadenza. The slow movement in D major, has been compared to a Chopin Nocturne. It is relatively short and almost at once complexity of figuration. The final Allegro vivace, opening in 9/8, contradicted in the second bar by the piano’s quadruple-time 12/8, continues this pattern of contrasting metres. The excitement of the opening leads to a more tranquil mood in a central section marked Andante ma non troppo, in the key of E flat. The original key and mood are restored as the concerto moves forward to its final optimistic F sharp Major.

Nathan Carterette, pianist, USA

B. Bartok Allegro Barbaro

B. Bartok Improvisations on Hungarian Folk Tunes Op.20

B. Bartok Allegro Barbaro and Improvisations on Hungarian Folk Tunes, op.20

Program Notes

These two works are ideal representatives, not only of Bartok's deep knowledge of folk tunes from Hungary and surrounding nations, but also of his genius as an inventive composer, who had a distinct voice in the sound of his music, as well as the theory.

In his long and involved research into the ancient songs of Hungary, Bartok all the while considered how these melodies could be used in higher levels of composition. He identiied three ways the composer might use folk melodies: as the main themes of the composer's work, harmonized and decorated by him but only enhanced, not surpassed by his invention; as a starting point, keeping the melodies intact but including on equal footing music of his own devising; or taking from the melodies the spirit alone, featuring no actual melodies but "permeated throughout" with the folk flavor.

Here are two works that aptly illustrate all three principles. The Allegro barbaro, written in 1911 (also the year of Schoenberg's Three Pieces op.11, Stravinsky's Petrushka, and Ravel's Valses nobles et sentimentales), is a work soaked in the folk atmosphere, with, according to Benjamin Suchoff, elements of Slovakian, Rumanian, and Hungarian folk music in its asymmetrical construction. it's a work performed often without nuance, which is strange because of the juxtaposition of irregular phrases - and within these phrases irregluar counts of "syllables" - which easily allows for a song-like rendering. Song-like, though certainly not "bel canto." But is bel canto the only way to sing?

The second work lies somewhere between the first two categories defined by Bartok. It presents folk melodies intact, along with much material of Bartok's own invention, though it must be recognized that he is writing always in response to the folk melodies. In a way they are the most prominent feature, and in another way, they are there to inspire his own creation. Like most categories in art it is not easily defined. Bartok said about this piece, "I reached, I believe, the extreme limit in adding most daring accompaniments to simple folk tunes."

The Improvisations are not so outwardly virtuosic as his Suite or Sonata, and probably for that reason are less played, but they are so characteristic of Bartok's deepest and most unique musical qualities. All eight movements take their starting point from a different tune, which is sung with Bartok's own harmonization (far removed from the kinder, gentler and perhaps "folksier" harmonizations of Brahms or Liszt), and then pontificated on - not developed in the traditionally Germanic sense, but "considered," and reacted to. Each piece is a dialogue between the broad umbrella of the folk melody, which by definition touches on experience familiar to everyone, and the personal feelings of the composer. There are innumerable poetic possibilities for this kind of drama: sometimes the two elements (public and private) come into conflict; sometimes they rejoice or mourn together; we feel in the dialogue nostalgia, melancholy, ecstasy, a wide range of reaction. This piece is actually a monument to Bartok's objective and subjective labor on unearthing the fertile soil of Hungarian folk music.

Finally, on a personal note, I had the opportunity to perform this piece in July 2004 in Hungary. Since the music we as pianists often perform, from Bach to Bartok for instance, is far removed from us in time, it came as a great surprise to me to find that the Hungarians knew the tunes, sang them, and still danced to them in "Dance Houses." For them, these folk songs are not a thing of history books and program notes, but living, breathing organisms, that have contributed to their lives since childhood. That the songs have survived the destruction and oppression endured by Hungary in the past century at least, is also a testament to their artistic truth, and universality, the qualities that inspired Bartok to many masterpieces.

ADOLPH VON HENSELT

Adolph von Henselt (1814-1889) is one of those paradoxical figures of music. Although his name sounds Austrian (from his paternal side), his family soon moved to Russia. Here, he became a far more significent force than one might deduce from his comparative obscurity (the reason for which is more attributable to the enormously gripping psychiatric difficulties to which he eventually succumbed, than to any lack of ability). One of the most concise outlines of his life was written by Thelma Godowsky for the reprint of this great concerto for Paragon Press..."Those that heard Henselt reported, his playing to be most poetic, possessing the most equally developed hands of iron strength and endurance ... a specialty of his was playing widespread chords (and passagework..). Being of an extremely nervous temperament, he seldom played in public. In his twenties, he went to Russia and lived and taught there until his death. Rachmaninov and Scriabin, among others, were his classmates under his tutelage. His concerto was often played at this time. The famed Gottschalk had it in his repertoire. Due to the extreme difficulty of the concerto, many pianists of the period were not sorry when interest in the work faded away - not because it lacked attraction or effectiveness, but because of its massive difficulty. Nevertheless, it is a magnificent, brilliant, and powerful concerto, and the publisher takes pleasure in making this neglected work of almost insurmountable difficulty, which sometimes proves of great discomfiture for the pianist, again available."

To understand Henselt, the composer, it is necessary to examine Henselt, the teacher. Like his later and more famous pupil, Rachmaninov, Henselt believed that performance, composition and teaching to be extensions of the same continuum of thought. Unlike Chopin and Liszt, Henselt wrote several pedagogical works which had two truly original features - he was the first in print, at least, to analyze technique in empirical scientific terma, and second, he quotes difficult passages from various composers (including himself), often making exercises out of them. One of the few of his works to survive the Russian Revolution, civil, and World Wars is a wonderful set of twelve etudes, which so captivated Theodore Leschetitzky (another pupil) that he taught them to all of his students (indeed, Leopold Godowsky, Benno Moisewisch, and Sergei Rachmaninov all recorded them, and championed his work). The genesis of his F minor Concerto is somewhat difficult to trace. In 1832, after studying with Hummel, he played a concerto of his own, which was afterwards destroyed. Clara Schumann listed "Henselt Konzert, Manuskript" in her repertoire. In 1844, Clara listed "Henselt 2tes Konzert.' Whether he produced each movement individually is unknown - what is known is its final incarnation appeared in 1855 when Henselt was praised as "the Russian Liszt".

By then, the "extremely nervous temperament" to which Thelma Godowsky alluded in her biographical sketch, had grown into full blown agriphobia (commonly known as "Sudden Panic Syndrome"). Ironically, his mental and physical acuity remained undiminished, As late as 1889, Henselt composed a set of choral motets which Scriabin thought so glorious that they helped inspire the latter's 3rd Symphony, "The Divine Poem". These motets have become lost, either to Russia's turbulent history, or, like much of his work, they became tragic victims of Henselt's own depression which often took the form of the composer destroying his own manuscripts. The ironic fact remains that when the world stage was finally open to him, Henselt was too seized by panic to leave his home. Psychoanalysis was in its infancy - even the legendary hypnotherapist, Dr. Dahl was a generation into the future. To compound the problem, Henselt began suffering from a form of writer's block - when an idea did come, he would censure it as unworthy. Rachmaninov wrote that..."perhaps this work (his concerto) was so nearly perfect that he felt he could never scale that height again" Nevertheless, he became a tragic figure. In the words of Raymond Lewenthal, Henselt became a "pianist who could not perform, and a composer who could not compose"...this in an era when the attitude of society towards those suffering from mental illness was far from compassionate. This frustration caused Mansell's behavior to be increasingly erratic, and

Despite his relatively brief and tortured career, Henselt still managed to leave giant footsteps in the landscape of Russian music, and this concerto, rich, opulent, and above all superbly pienistic is a glorious monument to the Romantic Era.

THEMATIC ANALYSIS

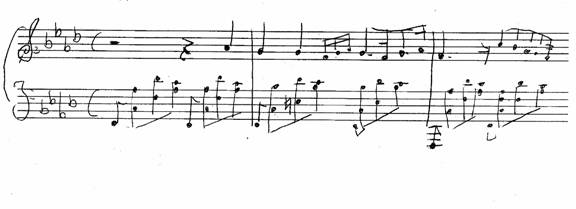

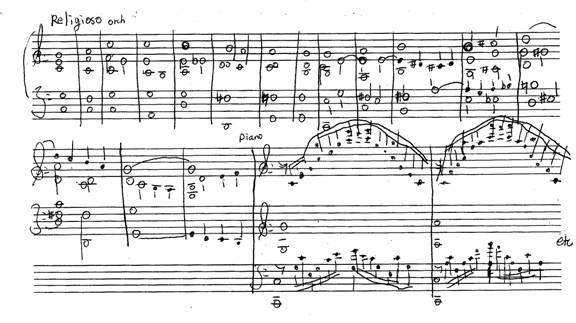

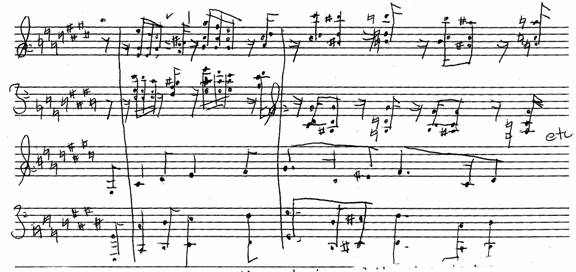

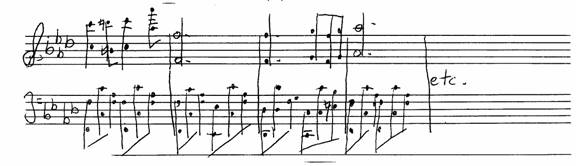

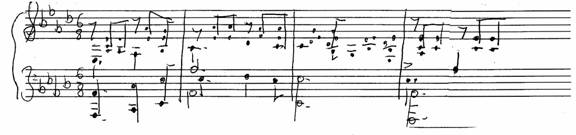

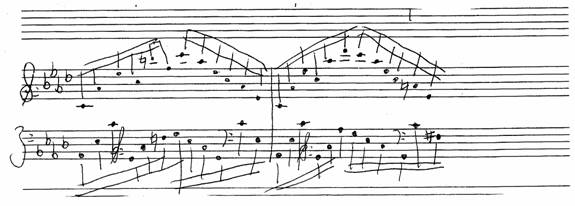

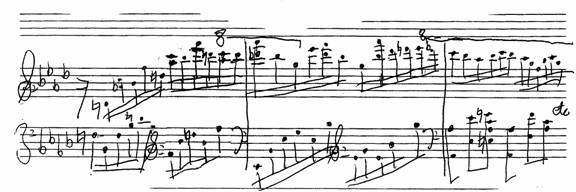

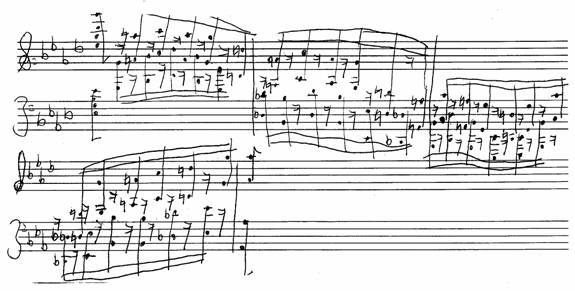

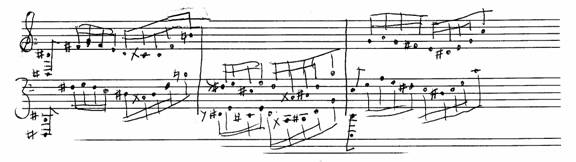

Like the best of Russian composers, Henselt often develops the most apparently simple thematic material in very elaborate and complex ways – a characteristic he ablely displays throughout the concerto. After a thunderous opening, he introduces the primary motif of the First Movement:

which after a brief, but impressive development, leads into the plaintiff, Schumanesque secondary theme in major:

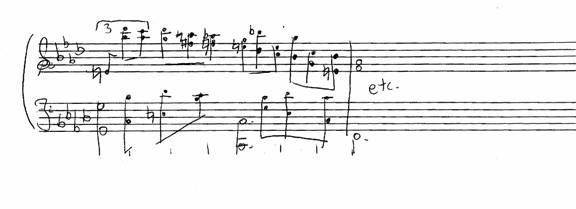

He quickly combines both of these themes, in the finest tradition of the Russian Romantic Concerto:

which brings the exposition to a brilliant close. From a compositional standpoint, here it gets very interesting, because where tradition would dictate a development of existing themes, Henselt introduces something entirely new = a fantasy within the movement itself. He introduces a choral motif based on the modes so prevalent in music for Russian Orthodox Church (the most famous example would be the muted chords in Mussorgsky's "Great Gate of Kiev"), first in the orchestra, then answered in full pianistic splendor:

Thoughts on Piano technique

What is piano technique? It is a set of means needed to give expressions to musical thought. For an interpreter, a player, the law is always the musical expression. Remember what Beethoven said to Czerny about his nephew "Above all bear in mind the sense of the musical phrase. Even if j have not thought very much j have realized that only in thi away are musicians formed".

Every aspect of a pianist's technical education must herefore stress this, and all the resources of the instrument must be brought to bear in giving expression to the throught contained in musical works and, at the same time, to develop the personal sensibility that underlies the birth of a true interpreter.

In my view, teachers must first ensure that their pupils acquire all the preparatory technical elements with the aim of developing and perfecting them. The study of piano technique, in the various and sometimes contradictorys ways in which it is pracitced

today provides confirmation of this truth. Music is perhaps the greatest art; music speaks, and we must succeed, with just ten fingers not two hands, in giving materials expression to the universal language.

It is necessary for the player to form a single entity with the instrument, by considering two natural factors that all too often are found to be in a state of antagonism instead of cooperation: the human body and the instrument.

It appears easy to play the piano, a key can be made to sound simply by depressing it, but to play as a professional, as an artist, is terribly difficult. We have to commit our minds, our heart and our hands to the same degree. If one part is missing, the balance is destroyed.

I call the work of building technique an "artisanal task". First of all, an artist is an artisan.

We have to construct a techinque based on our ten fingers, because all the production of piano music has been made for these ten fingers.

It is therefore necessary to remember that there is a very small but omnipresent mechanism in the universe know as order, and we must remember to fit this element of order into our musical work.

I shall start by addressing the question of the points of corporeal support in relation to keyboard. The whole body rests on three points of support: the feet, the position on the stool and, above all, the fingers on the keyboard. To have a good support, it is necessary to find the right balance; the contact with the keyboard is only possible

Every finger has its own expression and character. The sound always has to be expressive, it must express content and character. We

The continuous support is provided by the back and the shoulders, the arms are attached to the chest with the largest spherical joint of the back, which enables us to make every movement. Thus, the chest, the neck, the hands and the arms must be completely free and relaxed, and the emission of the sound cannot rest on any parts tha those j have just mentioned, because otherwise the flow of sound would be

The nerve endings is the skins are linked to the brain by a long, uninterrupted filament. Each point of the skin is linked to the nerve centers quite like telegraph line that terminate in a central station to light the "light bull"("la lampadina"). To achieve this, you

the last phalanx, the finger pat on the keyboard. At the end of the fall, at the moment to impact with the keyboard, a small mouvement has to be made to fix the position.

The comes the joint linking the hand and the arm, the wrist, which can move up and down, laterally and in rotation. Another most important joint is the elbow, which can be raised towards the body and is therefore the joint that gives the lenght of the arm.

The next is the shoulder, the only spherical joint permitting mouvement in every direction;

For his conformations and his position(situation) is very important of the hand mouvement. With the relax mouvement of the wrist we can pass from one to another position. The important mouvement of Portato. It necessary to learn to weight for different expressions

These supports are: the backbone, the shoulder blade for halls the shoulder for the forearm, the forearm for the wrist, the hand for the fingers. The support of the back is provived by the last vertebras and even very light touches are supported by the back and

The key to all these aspect is the position and muscular relaxation. The timbre of the voice will be poor, unpleasant, if the breath is badly controlled and the throat tigh, just as the sound of the piano will be bad quality(and the body effort excessive) if the weight

The manner of the attack of a key modifies its sonority.

The list of these works is both long and international, with studies produced in Germany, Russia, France, Italy, England and America by authors such as Kullak, Breithaupf, Rubinstein, Levinne, Neuthaus, Selva, Long, Cortot, Brugnoli, and Matthay; as well

The sound of the piano is of course already maid by the instrument, unlike strings or wind instruments. But it is possible for the intelligent and sensitive thoughtful pianist to modify the sound in a lot of way through an accurate work of the sonority. Every

Good intentions alone are no guarantee of mouvements that will produce the desired

There are never the immediate result of a affort, they have to be cultivated little by little, with patience, order, craftsman like work and love and care. A consciousness of perfection is the result of phenomena that develop within ourselves and which we

The free fall gives the deepest sonority. The use of this sound must always correspond to the musical intention.

The study of piano allow to us to increase our power of concentration and thinking.

A person who has acquired some knowledge without learning to thinks has done no more than accumulate zeros without a leading number to give them significance.

A reform of the teaching of piano technique in accordance with science is no novelty. Thanks to experimental analysis, we now can account for the influences that the pianist's touch exerts on the way the key is depressed. In particular, it is no longer a mystery why

Mary Jaell says: "We have to over come instinct to reach(get to) the awareness".

The hand is not flattened, but prepared in an arched, semirounded structure so that it can be estend it easily.

All the mouvements of the fingers, wrist and forearm are oriented to the positioning ofcontact. Considering the additional benefits to be derived - the acquisition of a beautiful and varied sonority and a variety of tone colour - the contact with the keyboard

Pianist may be grouped into two categories: those who are able to hear well and those who are not able. The first only seek to acquire digital agility, wrongly mis-taking this for technique; the latter pay attention to the immobility and stability of their posture and the way their fingers strike the keys. Technique is always

The study of the piano thus allows us to increase our powers of concentration.

The mouvements of his fingers for striking the keys with a "back and forth"mouvement of the fingers does not make the fingers independent of the hand.Every mouvement of the finger, needs to make intelligent use of the force thatproduces it.

We could offer many other examples of touch and mouvement but what j wish tostress(underline) is that the keyboard was invented not to separate the fingers

Our immediate recognition of the pianist's personality stems from a complex phenomenon whose immediate source is the pianist's quality of sound.

Do not try to form a whole in a mechanical fashion. Art has nothing to do with mechanical assemblies. The very core of art is the expression of a living thought. This is why the pianist must understand that all the nuances of the phrase are obtain through physical gestures.

The modern way of playing is much richer than the old one, but it has to be controlled much more and it is necessary to know the capabilities of the means that are available to do this. Searching in the human body for the means of obtaining different impulses, it has been found that the point of equilibrium for the modern performer lies in the weight, and that it can only be obtained through muscular relaxation.

Means of education based on psychological rules, relaxation, freeing the body from undesired tenseness, thereby permetting the will to be intelligently focused. These are the key concepts of the "musical" teaching of piano technique.

Remember what Rameau said: "every position contributing a special feature can be used to obtain the variety required by the expression".

It is necessary to study the mouvements in order to possess them and arrange them in order. Sincere teaching, loyal and intelligent use of the body to produce the sound of the piano, and the sound of the piano to produce musical expression.

The artistic truth and the physical truth come together and take on significance in the physiological truth the own meeting point.

Music is not only the science of sounds but the science of sounds is the material substance of music.

Hermira Gjoni , pianist, ALBANIA

Jenny Rroi, pianist, USA

EMOTIONS AND PIANO

Music is associated with the language of emotions. It makes us cry, dance, sing. Music speaks to us all and lives within us in our brain, in our consciousness, in our emotions, in our imagination. It is amazing that the music is such a language understood by people of all nations, regardless of age, race, religion or nationality.

An emotional interpretation is highly personal, connected to individual experiences. The depth and breadth of the hole person are definitely necessary for interpreting any composition properly. Is important to understand music influence on the emotions and the ways the music conveys emotions. They are an important component of music experience and there are many ways how the music influences the human behavior. The very word emotion always evokes happiness and other times sadness, fear, surprise. Most people can identify correctly the emotion of happiness or sadness when they listen to a musical passage suggesting such emotions. If the music can speak to so many different cultures, it is because there is in each individual an attraction to organized sounds. The composers, performers and listeners of every generation live “musical moments” together in ways that will put them into touch with the future.

The student should learn to think and feel musically at the very first stage of learning piano. The teacher finds the appropriate moment in each individual case. If a child is able to reproduce some very simple melodies, the most important thing is to make this first “Performance” as much as possible expressive and musical. This are the bricks which will be laid together and will build the future compositions. The child will learn from the beginning to play a sad melody sadly, a live melody lively etc. and should make his musical and artistic intention completely clear. If the young pianists will learn to recognize and perform this small fragment properly and with intelligence, they will as a progress meet the larger forms of composition with perfect understanding and will not be bewildered at the weaving together of many musical fragments into perfect whole. The student begins to understand that a composition that is beautiful as a hole, is beautiful in every detail and each detail has a sense, a logic and an expressiveness. They should try to play more intensively and with great emotions giving greater depth to his understanding.

To fully transmit this emotions the young pianists should learn from the beginning to play the study or exercise at a given speed and none other, with given strength and neither louder or softer. The aim of the study is to develop both the technique and the emotions. It will help immensely the young pianist that instead of an educational exercise or study to play with all the given nuances a real musical composition. His emotional state will be quite different, it will be heightened compared to when he will play useful exercises. And will be much easier to show him because his own intuition will tend that way, the tempo, the nuances and consequently the ways of playing that will be required for that given composition making it meaningful and expressive. This work will be the embryonic form of the emotions. Transmitting this emotions brings us to the work on artistic image, and this can be successful only if it is the result of the pianist continuous development musically, intellectually and artistically and as a result also pianistically. They will live with the composer for a period of time until they will thoroughly assimilate him. This includes the memorizing the score without touching the piano in order to develop the imagination and learning him to distinguished the form, the thematic material and the harmonic and polyphonic structure of the composition. It means using every means to arose the professional ambition of the young pianist to be equal to the best, developing his imagination. Only in this way the young pianist will be able to understand that a composition that is beautiful as a whole is beautiful in every detail, each detail will have a sense, a logic, and an expressiveness for it is an organic part of a hole. And to make the performance be emotionally moving, interesting there should be emotion in every note, and this will be learned from the pianist from the very beginning aiming not only at his intellectual but also at his emotional reactions.

The main demands of achieving beauty in a performance is simplicity and naturalness in expression. These two words are complex and their meaning is manifold we can feel their tremendous and decisive importance when they are put into effect.

The power of music on the human mind is routed in the very nature of the man everything is tinted by the colors of a subconscious spectrum, everything is endowed with emotional overtones which are unfailingly present and easily identified. This emotional quality, the subconscious state of the spirit is everywhere and in all the moments of the interpretation. All this components combined with the depth knowledge and love of the instrument will be able to recreate the artistic image of the composition.

In all good piano playing there is a vital spark that seems to make each interpretation of a masterpiece a living thing and will exist only for the moment. This vital spark that brings life to the notes is the intense artistic interest of the player. It is the astonishing thing known as inspiration. When the composition was originally written the composer was inspired and the performer will find the same joy in that moment something essential enters in his playing and he will be invigorated in a marvelous manner, and the audience will realize this instantly, because the audience understands when the pianist is inspired. One of the conditions that will help this situation develop in the best possible way is the fullness of human impulses and emotions. The most important thing beside the notes there is the soul. It is the source of the higher expression in music which can not be represented in dynamic marks. It will fill the needs for the crescendos and diminuendos intuitively.

Piano develops both, your emotions and your intellect. It also helps you getting to know yourself better. Recent studies has found that the most significant relationship between calculation, coordination and emotions lies on the fact that the first one (calculations, mathematics) are made in the right side of the brain, while the second ones (emotions) on the left. When it comes to piano, for example, piano enhances the connection between those two sides. Through the study of piano, this connection is enhanced. This happens for two main reasons. First of all, you need a greater hand coordination in order to play piano. So you need to enhance that. Your right hand and your left have to act independently. If you play piano and you train your brain, it becomes more and more effective on exchanging information between the two sides, since there must be a connection between them.

Music is a type of language. It communicates, almost universally, the language of our emotions. Every piece of music has some sort of emotion behind it. That is how the composer communicates to his listeners. We can play a piece without making any technical mistakes, but if we play detached from the emotions behind the song; we are making the biggest mistake of all. We are leaving out the most important aspect of the piece. And without that we will be unable to communicate what the composer intended.

Horowitz said that the music is behind the notes, not under them. You can play the notes as you would a typewriter; but where is the music? The music is behind the notes. The sense of the music is that when you open the score, the spirit of the music comes out the other side. You have to open the music, so to speak, and see what’s behind the notes because the notes are the same whether it is music of Bach or someone else. But behind the notes something different is told and that’s what the interpreter must find out. He may sit down and play one passage one way and then perhaps exaggerate the next, but, in any event, he must do something with the music. The worst thing is not to do anything. It is difficult to comprehend how some pianists are able to cover the gamut of repertoire from Bach to ultra contemporary in a short time. That is the reason that so much of contemporary piano music is often played with very little expression. Every composer who has something to say musically, says it in his way as no one else can say. Studying as much as possible material will help the pianist understand the best way to transmit the emotions that a composer wanted to give throw his music. One pianist felt that there something was missing with his interpretation of Sonata of Beethoven, so he sat down and red carefully all the documentations and all the letters of the composer to know him better. Than he was amazed how different the piece sounded. There he could feel the passion and meaning behind the notes. Almost immediately, he could sense the melancholy and emotion contained in the piece. He closed his eyes and focused on the emotions he felt when hearing the piece and this time, he played entirely immersed within the emotions of the piece.

Horowitz played the third concerto differently of how Rachmaninoff played it, the composer agreed with his interpretation because it was in the muse of composition and the pianist had felt from inside what the composer wanted to say. There in that interpretation was the atmosphere of pessimism of the Russians because of the physical and intellectual deprivation. And Horowitz putted all this into his playing.

When learning to play a particular piece, focus on the emotions you feel when you hear it for the first time. Are you happy or sad? Disturbed or delighted? Pretend you are the composer and this is what you are expressing to the world. Play with passion. You will not only take more enjoyment in the piece “you have to play,” but undoubtedly, you will be a better pianist playing even a more beautiful music.

Under different acoustic conditions, a piano sounds and feels different to the player, and in spite of an age of “planning” it is rare to find a new hall which is acoustically satisfactory for a piano recital. To have the most possible sound effect and emotions transmitted to the public the pianist may need to change even the weight of the keys and the disposition of their weight, which affects depth to touch. To “Feel” the touch of the piano keyboard is important to the player and the success of his performance will largely depend on whether he is comfortable with it. Different pianists like different pianos, different kind of actions. An audience is quite often unaware with what a pianist maybe contending when playing on an uncongenial instrument.

If we see only the mechanic side, then we must judge only on the basis of the instrument of the time of Chopin and Liszt where the pianos were so light to the touch that almost a blowing on the keys would almost produce the sound. The sound was smaller and that’s how it should have been, because the concert halls accommodated only several people and many recitals were given in private homes. Beyond the mechanics there is the real meaning of technique, is the sound, interpretation, tone, and musical line. It is phrasing, accent, melody and musical conception. You must find the right technique you must apply at this moment in this particular piece you are playing. For that reason it is important the way of expression on the instrument and the possibilities that it offers for a number always greater of emotions. Meyerbeer said: “The piano is intended for delicate shadings, for the cantilena, it is an instrument for close intimacy”.

With the expansion of audiences piano recitals are now often held in halls far bigger for the instrument. This also effects the emotions transmitted. Among all these varying conditions of pianos, the pianist has only his senses of duty to guide him to make the best in these circumstances. The pianist will give his maximum to transmit the emotions.

Another point in emotional field are the style and performance that are so closely connected with a composer style of writing and behoves a performer to identify himself as far as possible with the composer. Capturing all the different styles, trying to really know the artist the man his background, his thoughts, his feelings, his own letters are the best guide, this is the best way to understand and recreate emotionally his music. That’s what makes a re-creative artist’s life a creative one. When you play a recital with Mozart, Chopin, Debussy, Prokoffiev, you are playing music of four entirely different man, from entirely different backgrounds, entirely different styles and periods. It’s like being an actor coming out on the stage, playing four entirely different roles. You try to recreate the essence of Mozart, the essence of Chopin etc. That’s the great challenge of being an artist, to delve deeply into. And there is the other important part - the audience, the listener. The listener that’s include the artist himself.

Each composer has his own world of sound and emotions, according to the age in which he lived, the national characteristics discernible in his style and the type of instrument for which he wrote.

(Mozart) There are no emotions of depths, unhappiness, tragedy, frustration, anger, and despair that have not touched Mozart to the very core of his being. Nor was there any nuance, any form of delight that passed him by. The inspired musician will wed his life to the essence of the piece, demonstrating the glow, the swiftly-changing visions through the symbols that were the language of this composer.

( Beethoven) Surely there has never been a more angry young composer than Beethoven, particularly in the tension which is reflected in his early works, although he retained an irascibility induced by ill-health all his life. With his vigorous nature, never regarding the piano as a harpsichord with hammers, he had a more individualistic piano style than his predecessors, more legato depth of tone and his touch was far more weighty.

( Chopin) The romantic composers never hesitated to express their hearts on their sleeves. Small wonder that Chopin’s nocturnes have tremulously feverish quality at times, an expression of the exile’s homesickness, the consumptive’s anxiety. The B flat minor Sonata centers around the funeral march (emotions of grieving) and the other movements leading up and away from it. It might be a portrait of a young romantic hero. Despair, love and triumph figure in the first movement. The scherzo’s dark undercurrent of bitterness and fatality is relieved in the tender melody of the trio, by the vision of the beautiful beloved, a vision that is recalled in the coda of the movement. Romantic fatalism received no truer expression in piano music than this sonata. Pride and fearless courage are the emotion and essence of his national music. The Mazurkas and Polonaises optimize the heroes and their courage in the face of death or danger.

Enthusiasm and impetuosity are the most notable characteristics of Schumann, not only in his own music, but in his appreciation of that of others. His effervescent vitality was balanced by an introspective calm. His musical language is a mixture of impetuous warmth and reflective dreaminess.

Brahms sounds a deeper, more serious note then his contemporaries as was said of his preoccupation with melancholic themes: “He was never so happy as when composing about grave”. In some of his pieces, particularly in those of his last years, there is a feeling of personal complaint, that was prophetic for the upcoming of Mahler. His style of piano playing was massive. His works have tremendous energy fire and temperament. Like Chopin he hid his feelings behind abstract titles, such Intermezzo or Capriccio.

With the compositions of Claude Debussy and Moris Ravel at the end of the 19 century, French piano acquired an imaginative distinction which it has not reached since. The usual practice of coupling these composers together, while admitting their contemporary brilliance, fails to distinguish between their very dissimilar qualities. They are the last great writers in pianistic elegance. In the visual arts, whose creators were much more numerous, a corresponding response to color was evident in the paintings of Monet, Sisley, Pisarro and Gauguin.

The unconscious plays an important role in a performance. Sometimes happen that while playing, even though you have decided how to play the work, some nuance, some turn of phrase crept into the playing that will make the performance transcend to what you have never hoped. May be you have searched for ever and never found it, yet it was there. Some psychologists say that this is the result of intensive work, others claim that the ideas were lying in the unconscious all the time and merely needed triggering to come forth. I can say they were there and will seem to be most metaphysical in their origins, but this came out only with the help of the emotions. The music with all it beautifulness is in first row a personal happiness for the interpreter himself. The rapid growth of artistic level in search of an musical ideal, brings the perfection creating the creative magic of interpretation. It is this magic that during the “live” concerts makes gradually the audience to have a common emotional consensus with the pianist.

There is emotion on the moment of the silence at the end of a quiet work, before the release of tension by an outburst of applause, or tumultuous applause, which hardly wait for the last note of an exciting piece, sometimes closing over a work before it is finished. Now no longer a series of individuals, but a collective unit, the audience has become an active participant in the music. Would one of this individuals receive an equivalent sensation from the pianist playing to him in private? The outlines of the music might not be so sharp, the impression so vivid, without the tension created in artist audience by the sense of occasion. A good deal of the listener’s active enjoyment is created by the awareness of the audience around him, the collective concentration, the projection of the pianist personality. How flat it would seem to an audience if they were assembled to listen to a program of recordings? No heightened perception, no personal magnetism.

The intellectuality is tied to the emotions. Anybody who has ever tried to live with masterpieces of music for several years has become aware of what they are about, how they are constructed, how themes, motifs hang together in a movement, and how movements hang together in a Sonata, and has discovered that Beethoven sonata is tremendous intellectual feat and that the intellectuality of sonata is an integral part of the whole. It is an interplay between chaos and order. As a poet said : “chaos has to shine through the adornment of order” in a work of art. Without order there would be no work of art. If chaos is life, which surround us, the work of art is something which puts order against it.

Piano is a singing instrument that is capable of percussion. Is the one instrument in the world that is capable of singing and accompanying itself. There is and should be a real joy in trying to uncover all the secrets of this extraordinary instrument. It is capable not only as a singing and percussion instrument but capable of making all kinds of orchestral effects as well. The piano has this marvelous capacity all within itself and the pianist must think orchestrally. For example “Pictures at an Exhibition” of Mussorgsky for such a long time had no success because it was played as a piano piece rather than an orchestral piece on piano. That piece of music is an entire mural. It’s a huge, beautiful wall. But if we reduce its dimensions and emotions, it’s simply not going to be successful.

All great music comes from the heart. Chopin put it pretty well when he instructed his students to “play with all their soul, all their soul” this is what we have to do if we want to make really great music. As in life, the more of yourself you give to others, the more you usually will receive in return. Only than can music evoke fully the beauties and mysteries of this world. Are these moments of magic when the soul is full singing, and the technique and the imagination are all working in conjunction. And than the inspiration and emotions will burst in the music.

Thank you Rachmaninoff Prelude Op.32 No. 10 & No. 12 Will Play: Jenny Rroy

Bibliography:

Schenker Heinrich - The art of Performance

Barnett David - The Performance of music

Cooper Peter - Style in Piano playing

Simon Gjoni - Instruments and the art of Orchestration

Neuhaus Heinrich - The art of piano playing

Mach Elyse - Great Pianists

Cortot Alfred - Studies in musical interpratation

F.Liszt Apres une Lecture de Dante-Fantasia quasi Sonate

S.Rachmaninoff Variationen von 'Corelli' Op.42

L.van Beethoven Klaviersonate Op.28, D-Dur

Home from Home by the Lakeside

Sergei Rachmaninov and his family at villa senar

When Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov - better known to the world as Lenin - returned to Russia in 1917, there were many to whom the ensuing revolution was unwelcome and who emigrated at this time was the composer, pianist and landowmer Sergei Vasilyevich Rachmaninov. Passing through Stockholm and Copenhagen, he eventually reached the United States in November 1918 and quickly came to prominence as a pianist, especially in the Classical and Romantic repertory (with particular emphasis on the period from Beethoven to Chopin) and as an interpreter of his own works. A review that appeared in the Boston Evening Transcript in December 1918 marked an important first stage in this development : "No more impressive figure has crossed the stage of Symphony Hall these many years than Mr. Rachmaninov [...]. Obviously Mr. Rachmaninov lives very much within himself, wears no surface-moods and emotions, cultivates no manners for audiences, shuts himself from the world except so far as his music and his playing may reveal him."

However enthusiastic Rachmaninov may have been about the manifold opportunities afforded by the New World, there was none the less something that the nature lover in him missed. "I've grown used to this country and I love it," he wrote to a friend in Moscow, Vladimir Robertovich Vilshau, "but there's one thing it doesn't have - quiet." Rachmaninov's packed concert schedule placed him under tremendous strain, not only as a result of the concerts themselves but because of the travelling involved, and it was only during the long summer breaks that he was able to get away with his wife, Natalya Alexandrovna, and their two children, Irina and Tatyana, and to enjoy the peace and quiet that had become increasingly necessary to him. By 1924, the political climate had become less charged, and from now on the family would return to Europe each spring, on each occasion taking with them two important objects:Rachmaninov's Steinway Pianino and the family automobile. The composer would then rent a luxury villa in the country, where he could work and relax undisturbed and where there was plenty of room for the many visitors who regularly called on his steadily growing family: Irina had mariied Prince Pyotr Grigoryevich Volkonsky in 1924 and eight years later Tatyana married Boris Yulyevich Konyus, the son of a childhood friend of her father's, and it was not long before the house was filled with the sound of grandchildren playing their boistrous games.

In 1930 the writer Oscar von Riesemann visited the Rachmaninovs at their holiday villa, "Le Pavillon", at Clairefontaine near Paris. Riesemann wanted to write the composer's biography, and when Rachmaninov agreed to his request, Riesemann reciprocated by inviting the family to visit him in Switzerland. They were so taken by the beautiful countryside around Lake Lucerne that they immediately decided to build a house there. Rachmaninov bought a plot of land in the village of Hertenstein on the lakeside, and between then and the outbreak of war 1939 the house - called "Senar" after the names of its owners, Sergei and Natalya Rachmaninov - was a summer refuge and a place for creative work and play.

In the event, building work on the new house dragged on, so that the Rachmaninovs spent the summer of 1931 back at Clairefontaine, where the composer completed his last great work for piano solo, his Corelli Variations (the Theme of which is not, in fact, by Corelli himself, but was borrowed by the latter from an old Iberian folk tune). It was Rachmaninov himself who gave the first performance of this new piece in Montreal in October 1931 - one of the rare occasions on which he performed all 20 variations: later he regularly omitted individual sections whenever it became clear that the audience was not concentrating or when they began to cough unduly.

By 1932 the Rachmaninovs were able to move into a part of the Villa Senar that had already been completed. In a letter to his sister-in -law, Sofiya Alexandrovna Satina, Rachmaninov summed up his feelings of enthusiasm at life in his new home: "Of our four days here two have been very hot, and two have had uninterrupted rain. Today for instance, it's been pouring since morning, and it's now seven in the evening. Nevertheless, I feel wonderful. I walk a little [...] and I work a lot. [...] Here is the peace and quiet that I need."

It was this peace and quiet that the family's sole wage-earner could scarcely find any longer, now that the Wall Street Crash of Black Friday - 25 October 1929 - had wiped out part of his fortune in shares. The economy was in recession, and art, too, suffered in consequence. Often enough Rachmaninov would travel across half a continent, only to find himself performing in half-empty, badly heated halls. And increasingly frequent and violent headaches were now beginning to torment him. The Villa Senar was consuming far larger sums of money than had originally been planned, and in the autumn of 1932 Rachmaninov gave no fewer than 50 concerts to mark his forthcoming 60th birthday and the 40th anniversary of his public debut as a pianist. The following years, too, saw almost as many concerts, even though his strength was slowly failing and his American star was no longer in the ascendant: a new virtuoso had appeared on the horizon and was soon to eclipse the man who was not only a fellow countryman, but also a friend and mentor. His name was Vladimir Horowitz.

For all their professional rivalry, the two pianists shared a common love of Steinway pianos. (It was at Steinway's New York premises that the two men once performed Rachmaninov's Third Piano Concerto on two pianos, an event that caused crowds to gather outside the building.) And when a brand-new grand piano arrived at the Villa Senar in 1933, it was, of course, a Steinway. "The piano looks splendid to me," Rachmaninov wrote to one of his friends in New York, Alexander Greiner.

This instrument still stands in Rachmaninov's former study, together with his desk, a landscape painting, numerous photographs of the composer, the famous drawing of his hand and, finally, his death mask.

Here in Switzerland in 1934 Rachmaninov wrote perhaps his most famous work for piano after his concertos and the Etudes-Tableaux, and the last solo piece for his own instrument - the Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini for piano and orchestra. Once he had finished work for the day, Rachmaninov would often leave the house and go out into the wonderful garden that he himself had laid out. There, among the cypresses, larches, silver firs, birches, maples, rose bushes and weeping willows, he found the peace and quiet that he longed for. In the distance were the mountains, while the lake glistened at his feet - it was a veritable idyll. It is easy to understand, then, that it was with a heavy heart that Rachmaninov left Villa Senar for New York on 23 August 1939, the eve of Hitler's non-aggression pact with Stalin. He was never to see the villa again.

Lotte Jekeli, pianist, GERMANY

"Leos Janacek and his piano cycle ‘In the Mist’"

Janacek was born 1854 in Hukvaldy and died 1928 in Ostrava. His center was Bruenn, where he started his career which was to bring him while yet he lived to international renown. He studied at the organ school of Prague before going to complete his studies in Leipzig and Vienna. 1881-1919 he was director of the new organ school in Bruenn and it was entirely his merit that this school became an independent Conservatorio after the foundation of the Czech Republic in 1919. From 1919-1925 he was professor of composition at the Bruenn-branch of the Prague Conservatory.

Only in 1874 he was able to afford his own piano but already one year later he had sat the examination for this instrument. In Leipzig he continued his piano studies and in 1880 his first composition for piano appeared: the variations in b flat major, dedicated to his fiancée Zdenka and first performed by Janacek himself in the Gewandhaus Leipzig. The Moravian dances appeared 1892 and breath the same atmosphere as act 1 in his opera Jenufa.

Only after having finished this great opera “Jenufa” he came back to the piano. In the time from 1901-1942 he wrote the 3 main cycles which constitute his most important pianistic legacy: the sonata I.x.1905, his most popular cycle ”On the overgrown path” and finally the 4 pieces “In the mist.” This was written before 1912 and published 1943 as a bonus for the members of “The friends of Art Club” in Bruenn. It was first performed therein 1914.

In shattering the classical unities Janacek went far beyond the folkloristic roots of his Moravian homeland, which he had begun to collect and study 1888 with his friend Frantisek Bartos. Already in 1894 he had some up with the theory postulating the development of rhythm and melody from the colloquial language. Where ever he happened to find himself he would notate the natural rhythm and melody of song and speech in their emotional context.

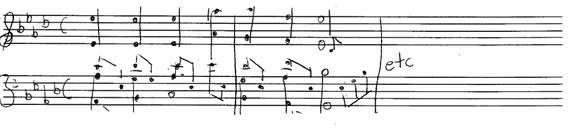

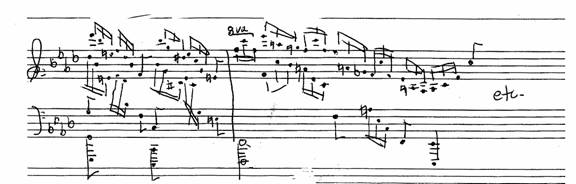

By the time of the four pieces “In the mist” Janacek had matured into a more consistent integration of his resources with a form made even more compact by means of ostinato figuration and systematic repetition. Instead of traditional motivic and thematic work he builds up progressions of individual static chords, which we find occupying center stage in many more pieces than just in the opening of this cycle. Here the six-four chord becomes the second main theme – example – and develops into further static chords over ostinato figurations in the left hand – examples – thus giving the accompaniment its peculiarly insistent character and leading to an impressive climax. In the second piece we have the systematic repetition of the main theme reduced to hemidemisemiquavers with real impressionistic effect – example – Another means of hightening intensity is his way of working with fragments, thus releasing thrusting new quanta of energy which at the same time tests and strengthens the overall context. Much of this energy is punctuated by rests, the momentum of the sound is carried relentlessly forward. Nr.3 has a genuinely folklike theme which is repeated immediately in the left hand in another key – interrupted by a fanfaremotiv. Nr.4 contains a splendid example of a speaking melody for its main theme. Here as throughout in his oeuvre Janacek turns language into music, giving his music the power and immediacy of the spoken word. The theme may be well repeated in a myriad variants of dynamics and rhythm resembling the changing colours and inflections of rezitative as in nr.3.

Sonata op.27, No.1 by L. v. Beethoven

Subjective aspects concerning the exceptional position of this particular sonata in the works of Beethoven, as developed from my own experiences in working with and playing this sonata

The Sonata “quasi una fantasia” in E flat Major is certainly not one of the most popular sonatas by Beethoven, resulting in it rarely turning up in programs, be that in concert halls or in recordings.

However, nobody denies the mastership of the composition or the beauty of this piece.

The reasons for this phenomen are perhaps the technical, but definitly the musical requirements and challenges of this piece.

The first movement is, from a musical point of view, the most difficult and exceptional of the four movements which Beethoven specifies to be played without interruption. (It is probably the first sonata by Beethoven where the movements cannot be performed separately and which bears as close a resemblance to the sonata-form of the romantic period where a sonata became more of a unified whole.)

Also, it is the only first movement of all sonatas by Beethoven which is structured with such little musical tension in the first and last part of the piece. A fast and forward pushing Allegro-middle part interrupts the Andante only briefly, so that the character is mostly influenced by the longer Andante.

A meditative, improvisative and dreamy theme in variated forms characterizes the piece. The music gives the impression that it is nearly static in sound, the only motion being given by the flowing left hand.

Here the dynamic pp is not an exception but the rule and written by Beethoven in every phrase anew.

This continously written dynamic pp can be also a warning for the interpret: The simple melody and harmonies which lead always back to the tonic would sound banal in a “normal” mp or mf.

We can find in both Andante parts in the first movement twelve times(!) phrases which end in the full cadenza with tonic E flat Major. This is a special task for the interpret. One has to lead the phrases to these endings but also over them to the next phrase not to loose the unity of the piece.

In the same time the pianist has to give the impression of a hovering, improvisatived and spontaneously created music because the “quasi una fantasia” character starts to live like this. Now could be described very detailed how to reach this ideal of interpretation. Here I want to mention just two aspects because they influence the interpretation a lot and are differently performed by all the various artists:

Beethoven writes a 4/4 bar, alla breve which should not lead the pianist into playing too fast; the deeply relaxed and completely peaceful atmosphere would get lost. Nevertheless, in performing the alla breve with a very light second beat whilst staying calm, one can achieve the necessary lightness.

Beethoven, op.27, 1 -2-

The second aspect concerns the relationship of the right and left hand. In this case the right hand has the principal theme with the main melody and harmonies while the left hand accompanies with an independent flowing voice which indicates the motion.

Here it is important to articulate the left hand differently from the right hand, for example the last note in the L.H.- phrase (bar 2, 3 and similar bars) has to be short, as written, while the right hand continues with a soft and longer chord. The right pedal has to be used after the short note in the left. Like this and with two different directions in the sound and phrasing one can achieve the two levels between both hands which again supports the hovering character of the theme.

In my opinion, the beauty and the awareness of this unusual movement can be realised only with these aspects of interpretation.

The second movement Allegro molto e vivace continues in providing the interpreter with musical and theoretical challenges. The archaic sequences are reduced on broken chords in both hands which, are at least in the first part, rhythmically completely even. The harmony-sequence reminds one of a Chaconne from the Baroque period while the extreme tonal range give a nod to the future.

This music can only live when the interpretation shows the shadow-like, running figures and the mysterious character of this piece.

To effect this the pianist has to play with gliding fingers, close to the keyboard and in the piano-part never too deep in the keys.

Also here Beethoven created conditions of hovering which are part of the composition: The beginning of the movement is not- like it seems to be – also the first emphasis but has to be played like an pick-up. The first classical period starts only in the second bar and so are all strong points one bar later than expected ( the first in bar 4, after always every second bar).

To support the ghostly atmosphere and darkness in the sound it is also important to play the legato-quarters with possibly no accents. One could bring out some nice top- or middle voices (like some pianists do) but this would be counterproductive to the obvious sense of this music.

After a short middle part the exposition returns but this time syncopated and split in staccato (left hand) and legato (right hand). Like this the part (bar 89-140) seems to be not only two times but ten times faster then before. To succeed in this technical challenge, it is necessary to keep the tempo perfectly and not get lost in an uncontrolled accelerando.

Only in the third movement Allegro con espressione the sonata reaches the conventional form and becomes obvious. A beautiful melody in full cantabile over low bass octaves and chords leads into figurations, a high trill and an attacca into the final.

The freedom of the quasi una fantasia-character before ends now in the answer of all musical questions. The 4th movement Allegro vivace has more bars than the three movements before together. It is from the technical or pianistic point of view the most difficult but in musical aspects the easiest movement.

The form is clearly structured and every musical idea is built upon the previous one in a logically clear fashion and developed likewise.

A continuously moving and motorically active left hand is apparent to the listener throughout the piece.

Beethoven op.27,1 -3-

The joy of playing the movement lies close to virtuosity and gives one a true sense of a Finale Sonata. This movement is most likely to be the first of its kind in this form, which thereafter took on an immense importance in the 19th century.

For an appropriate interpretation one should avoid playing the movement too introverted.

The stormy, fresh, accelerated-tempo character which is supported by many sforzati and dynamical contrasts has to be emphasised.

The return of the third movement’s primary theme and tempo (bar 256) make the quasi una fantasia clear. Here, Beethoven writes Tempo I - at this point, he means the Tempo I of the third, not the 4th movement. Once again, this indication shows Beethoven’s concept of an entire fantasia-sonata without separation in the movements.

Nancy Lee Harper, pianist, PORTUGAL

"The Interpretation of Manuel de Falla's Fantasia baetica"

INTERPRETING MANUEL DE FALLA'S

FANTASÍA BÆTICA: An Introduction and Masterclass

By Nancy Lee Harper ©2004

INTRODUCTION

In this day and age of pianistic pyrotechnics, Falla's chef d'œuvre still remains as illusive and daunting today as it was 75 years ago when it was commissioned by and dedicated to the great Polish pianist, Artur Rubinstein. Shrouded in bad luck, Rubinstein was unable to learn the piece in time for his Barcelona concerts in 1919, giving the premiere later in New York on 20 February 1920. The work was destined neither to have the impact nor become the mainstay of his repertoire as other works in his repertoire. Rubinstein played the Fantasy a handful of times, abandoning it, complaining that it was too long, too difficult, had too many glissandi, too many guitar and flamenco figures, etc.. If the truth were known, Rubinstein probably did not have the same audience success as with his version of Falla's earlier work, the "Ritual Fire Dance". It seems that he never recorded the work.

Although the Fantasy is now played by those pianists who wish to have a musical and technical challenge, it cannot be considered standard fare on the concert menu, nor in competitions. Why is the Fantasy so pianistically polemical? How does one arrive at an authentic interpretation? Not easy to answer, these questions require some knowledge about the work's history, structure, and musical elements.

Historical Background

Situated between the great virtuosic pillars of the piano repertoire, such as Albéniz's Ibéria (1906-1909), Ravel's Gaspard de la Nuit (1908), Alban Berg's Sonata, op. 1 (1908), and Charles Ives' "Concord" Sonata (1909-1915) Falla's Fantasía bætica has been described as a kind of Spanish Islamey and an Andalusian Fantasy but not an historical evocation. The large-scale work is definitely the most abstract of all of Falla's solo piano pieces. Difficult and uncomfortable under the hand, the question arises: "Why didn't Falla write something more 'pianistic'?"

Full of guitar figures, the Fantasy belies its name with its rhapsodic nature. Not a traditional improvisatory fantasy in the sense of Frescobaldi or Louis Couperin, the work also does not emulate the fantasies of Bach, Haydn or Mozart. Rather, it is more akin to the grand romantic style found in the works of Schubert, Chopin, or Schumann with the suggestion of improvisation or spontaneity. The adjective bætica was added when, in 1922, Chester publishers wanted a more descriptive title. Falla was adamant about the spelling with the diphthong in order to show the ancient Roman name of Andalusía that included the areas of southern Iberian Estremadura and some parts of Portugal.

The circumstances surrounding the genesis of the work are fascinating. Falla had become an international figure from the time of his Paris years (1907-1914) when his opera, La vida breve, attracted wide attention. Back in Madrid at the onset of World War I, Falla began his Andalusian period (1915-1919), in which he composed some of his most famous works, El amor brujo (Love Bewitched), Siete canciones populares españolas (Seven Popular Spanish Songs), El sombrero de tres picos (The Three-Cornered Hat), Noches en los jardines de España (Nights in the Gardens of Spain). Falla was greeted warmly, but cautiously, by the proud and fickle Spanish press. He was criticised as being "Frenchified" with there being some truth to this criticism. Even before his sojourn in Paris, his idol had been Claude Debussy, who befriended and counselled him. Paul Dukas opened many professional doors for him in Paris. And who better would understood Ravel than Falla? Indeed, Falla is reported to have said that without Paris he would have remained buried in Madrid and his score for La vida breve locked away in a drawer.

Ansermet-Rubinstein-Stravinsky-Debussy influences

The Fantasy was born as the result of Stravinsky's financial problems, due to the closure of his Russian publisher at the beginning of the Russian Revolution in 1917 and the ongoing WWI. On 10 March 1918 the Swiss conductor, Ernest Ansermet, wrote to Falla, asking him to contact Rubinstein, who was then in Madrid, to see if they could find a way to assist Stravinsky. Originally the idea was that Rubinstein would purchase Stravinsky's manuscript of L'Oiseu de feu (The Firebird), but instead he had a "better" idea — to commission a work from Stravinsky (Piano-Rag Music, 1919) and a work from Falla (Fantasía bætica, 1919).

Coincidently, two weeks after Ansermet's letter, Debussy died on 25 March. Falla surely must have felt enormously this loss, for Debussy was his mentor, friend, and idol who wrote exquisite Spanish music without ever having visited Spain. Is it possible that Debussy's death influenced the composition of Fantasía bætica? Outwardly there is no direct evidence to support this supposition. After all, it was the guitar that Falla chose to eulogise Debussy in Homenaje. Le tombeau de Claude Debussy (1920), the first modern guitar piece (also written for piano). However, upon closer examination of the Fantasy many French influences will be ascertained, especially that of Debussy.

While the exact date of the composition of the Fantasy is not known, it is confirmed that Falla composed the work during 1919, in three or four months. 1919 was bitter-sweet, bringing both great happiness and deep tragedy to Falla: international accolades for Diaghilev's prodcution of El sombrero de tres picos (The Three-Cornered Hat) with the Ballets russes (Massine, Kasarvina, et al) and decor by Picasso; the death of both of his parents (father in February and mother in July); and the final rupture with Gregorio and María Martínez Sierra, the couple with whom he had collaborated on many projects (El amor brujo, Fuego fatuo, El sombrero de tres picos, amongst others).

The Fantasy marks the end of an era, as well as the beginning of Falla's most mature and highest level of composition, one in which he would search for a more universal language and create his greatest masterpieces — El retablo de Maese Pedro (1923) and the Concerto for Harpsichord or Piano, Violin, Flute, Clarinet, Violoncello, and (1926).

MASTERCLASS

Often in approaching a work, the interpreter will search out recordings by the composer. While Falla did play the Fantasy quite brilliantly according to those who heard him in private, unfortunately there are no recordings left by him. Nor were there public performances by him that could have had critical reviews, as was the case of his Concerto.

Therefore, without a recorded model by the composer (sometimes not so helpful), an authentic interpretation must be gleaned from his written indications in the score, of which there are many. Musical form, melodic-harmonic-rhythmic-stylistic characteristics, textual matters, ornamentation, pedalling, fingering, amongst others, are important to consider. The Spanish song and dance flamenco tradition is especially necessary to understand.

Contextual Considerations: Stylistic Features: Spanish, French, or other?

What is readily apparent upon the first hearing of the Fantasy is its strong Spanish flavour. The imitation of the guitar is paramount, as well as the suggestion of the cante jondo, the "deep song" or flamenco tradition. These are Andalusian songs and dances (tangos, malagueñas, rondeñas, siguirillas gitanas, soleares, etc.;specific to the Fantasy are the bulería or bolero; seguidilla; fandango; guarija; siguiriya; soleá;), whose style of execution includes gutteral exclamations ("Ay"), melismas, jipío - voice break of the cantaor (singer of the cante jondo) and quejio or quejido (lament). One aspect to remember is that these songs and dances are usually not separate entities but rather are often combined into one genre. Included in the flamenco tradition are the toque jondo or "deep touch" (the instrumental equivalent to cante jondo) and the baile jondo (dance equivalent) with its taconeo (heel/foot stamping). Also, techniques like hemiola are integral to some types of song-dances, as are ornamental melodic figures such as accaciaturas and echapées.

Guitar influences impregnate the Fantasy, such as: punteado — guitar plucking; rasgueado -guitar strumming; copla (poetic interludes); falsetas — guitar "coplas" that introduce or are played between the vocal parts of the cantaor/ra (lead singer). Chords based on tuning of the guitar strings (e-a-d-g-b-e) are frequently found. (Example 1)